A short time before German occupation in Prague, Czechoslovakia, family man Karl Kopfrkingl is looking to attract new customers to his Crematorium, a business he manages. He sees his work as spiritual, believing that by burning bodies he can free the souls of the dead from suffering, and enable their reincarnation.

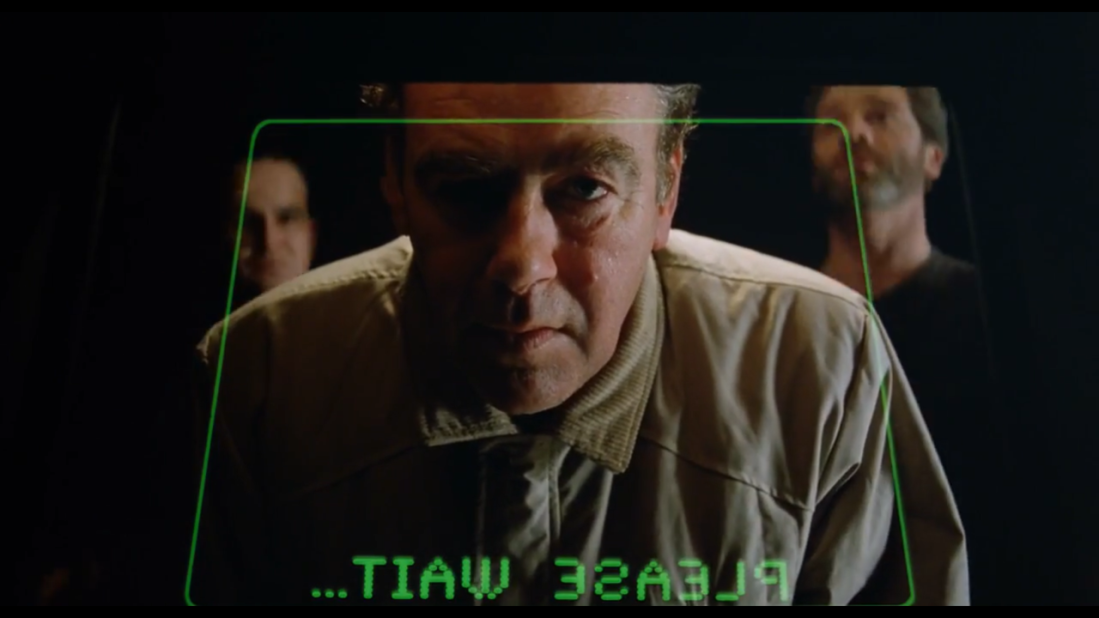

At a promotional event for his ‘Temple of Death’ as he labels it, Karl is reacquainted with old war compatriot, Walter. Walter is a successful bureaucrat and German sympathiser, who seems keen to bring Karl round to his way of thinking.

That’s all the essential information you need to know, and it’s packed tightly into the first few scenes, through an almost constant monologue, which is quite difficult to follow if you’re constantly glancing down towards the subtitles. More difficult still, because the visual style is extremely distinctive.

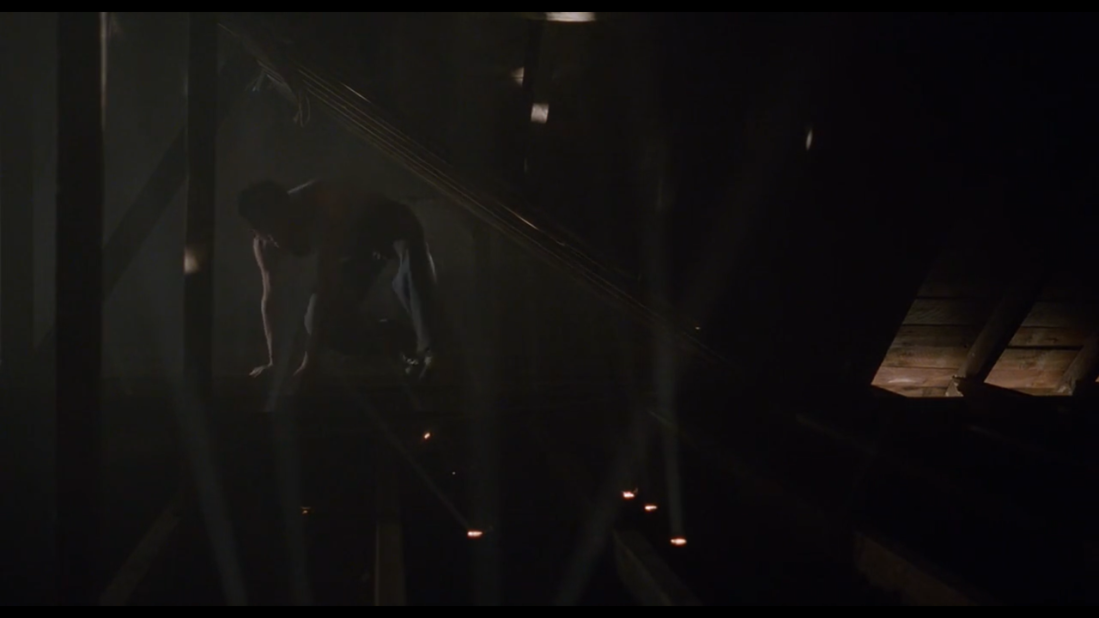

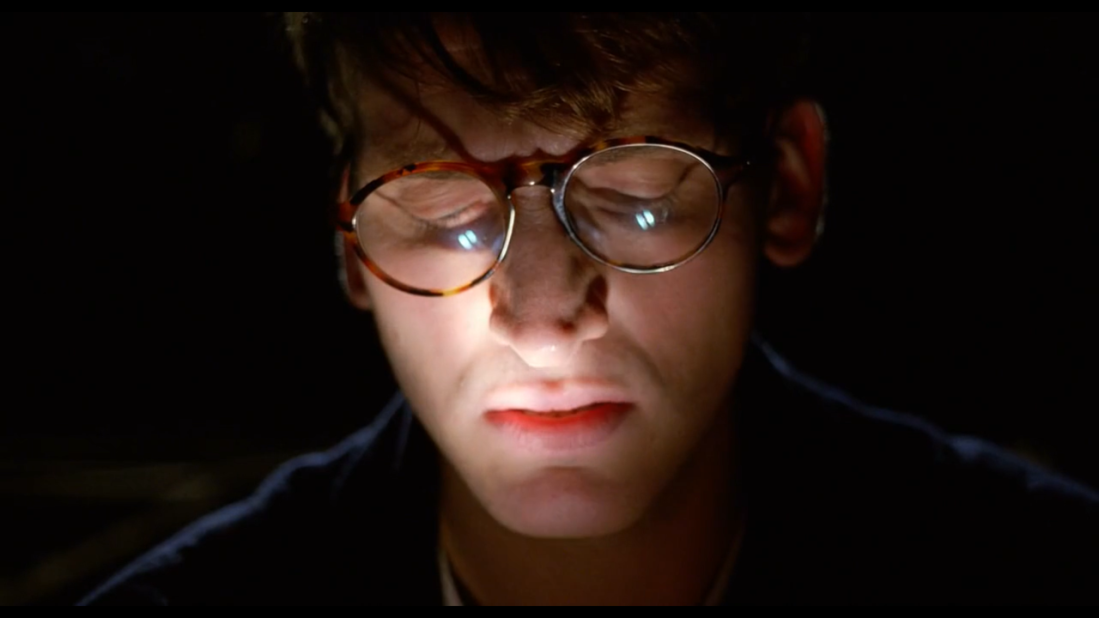

Director Juraj Herz bulldozes through as many cinematic conventions as possible, and comes back again to kick them in the teeth. The story is essentially about Mr. Kopfrkingl’s spiral into madness and fascist radicalisation. He’s extremely menacing and controlling, but impressionable and child-like. With chubby cheeks and paunch like a wrinkled cherub, he handles his food with his hands, he touches people’s faces like John Travolta in Face-Off and combs his perfectly slicked hair with delicacy. For a fan of the Dalai Lama he’s pretty material, with a tenderness for music, animals and a fixation on naked women. All his mannerisms grotesquely indulge in sensory pleasure and assert control.

He’s creepy, and brilliantly played by Rudolf Hrusínský. A threat to everyone around him, not because he’s a psychopath with a grand plan, but because he’s deluded, morally fragile and a man of respectability. At the beginning of the film I might describe him as someone who perhaps enjoys his job too much, but all it takes a friendly fascist and a few treats for him to adopt a completely new ‘higher moral code’. His selfishness and obsession with death sweep aside any principles he apparently had for his country his family, or human life.

Karl’s empathy may have died in the Great War in which he fought. To see so many people die might have corrupted his conception of the boundary between living and dead. So that he doesn’t recognise its significance.

If the film is only meant to be about Karl’s corruption then i think The Cremator has a similar minor issue as The Shining, where Jack Torrence comes across as a complete nutcase from the opening minute. Yes, Karl’s deep monotonous drawl is unmistakably evil. Karl’s family are also the most passive and oblivious bunch of people, it’s hard to suspend your disbelief sometimes, the direction and script give the whole film an alternative kind of logic, but they should have resisted more.

We see the whole film through his eyes or through the madness of his immediate surroundings. We slip through time, from scene to scene with the matter-of-fact-ness of a dream, we are never completely sure of where we are or who’s eyes we gaze through. Sounds like it could get exhausting or repetitive but through the expert and exact application multiple cinematic techniques, Juraj Herz definitely make film goo.d

Herz exploits our assumptions from cinematic language about the geography of the scene, montage, the position of the camera, character’s eye-lines and dialogue to transport us through the film like a dream. He repeatedly uses zooms to reveal or obscure information. For example when a character is framed in tight close up with heavy bokeh, Director Juraj Herz knows that we’re not aware of what’s in the background specifically, so although dialogue continues in the scene as normal, Herz may have taken us to a dfferent time and location. By contrast, when Herz chooses to zoom out on a character, he will intentionally reveal information about the scene that adds new context.

In the middle of the film, there is a stunning sequence where we slip from a Jewish musical ceremony, to Karl’s dining room, to a brothel, in the space of about two minutes. To transport us, Herz allows a character to physically whisper into Karl’s ear from another scene, and then spins us clockwise without a visible cut, into Karl’s Dining room. We then cut to an over the shoulder of Walter, then a Close up reaction with bokeh which transitions to yet another location.

Once he’s in the brothel, Karl starts to give away information about who among his employees are against the German Reich, this seems a little out of character at this stage, until Herz zooms out to reveal that Karl has been receiving drinks all night long.

Sometimes Herz will also disguise a POV shot to further disrupt reality. Here we have a wide angle shot of Karl leaving the bathroom, followed by a mid of another Karl in a different costume. Following this, Karl has a conversation with his clone. (very weird)

Herz gets away with it because the film is edited rapidly, with an almost constant stream of dialogue from Karl and music to bridge us over the cuts. If I spoke Czech, it would be a breeze to sit through, but the subtitles can make it hard to follow at times.

The framing is also very distinctive and consistent if you categorise them. The wides can take on a fish-eye quality and are geometrically arranged, the close ups are zoomed right in and the face dominates the frame, uniformally taking up about 3/4 of the space. Herz isn’t afraid to let characters stare down the barrel and also act naturally within this frame. It can sometimes feel like documentary photography. The mids are often tilted up from just above the waist, so faces are slightly high. Mids feel the most fragile because they are most often used to transition to more psychedelic feeling shots and sequences.

Given that the film was made in the late 1960s, a generation on from the second world war in a Czechoslovakia behind the iron curtain, the film takes on a much darker subtext. With a high presence of Jewish actors and non-actors who would have lived through the ghettos and the camps, and who’s parents would have been about the same age at the same time when the film is set in the early 1930s. There is an obvious analogue between cremation and the death camps, Karl’s logic and escalation is similar to how Nazis justified their actions, seeing Jews as subhuman would infer their genocide as a mercy. Karl is running a business which must become scalable and more efficient. In a particularly powerful moment, he describes an ultra-efficient crematorium, capable of blasting 500 people, with souls that would “Gush” from its chimneys.

The Nazis used bureaucratic language to dehumanise the people they slaughtered, so the use of organic/natural/indulgent language to describe something mechanical is quite a clever reversal. Ironically Karl’s unabashed evil contrasts with the Nazi’s relatively innocent lust for power. But under close scrutiny, the Nazis will happily exploit fanatics like Karl.

I don’t know how much wholesome, fibrous historical drama there is in The Cremator, it’s really a genre film, a Psychological Horror with a lot to say about the past and the present it exists in. If you’re generally into Psychological Horror, (shout out to Derren Arenofsky’s ‘Pi’) then check it out, it’s remarkable, don’t let the subject matter put you off.